I had arrived in The City over two years earlier, still glowing from a momentary flash of fame back in Albany - winning first prize in a big regional show for my Motorcycle Painting; still basking in the afterglow of all the news, reviews and howdy-do's that followed. In those brief, heady moments, I knew I was destined to become big - BIG - BIG! and of course, the only place to do that in the art world was the Big Apple. So I packed my gear and headed south - down the Governor Thomas E. Dewey Thruway, to Gotham. The Emerald City. Babylon. Thus began my journey into the first level of the inferno.

It took me a few months of floating around town, staying with friends, scratching together some cash, hunting for a space, etc., until I found an empty storefront in the East Village, just a few doors off Tompkins Square on East 10th, where I began to set up my studio. The year was 1968, the virtual peak of the cultural orgasm known as The Sixties, the psychedelic revolution, the countercultural movement, Woodstock Nation, whatever. Like many before me, I arrived in The City as a small town artist with big dreams and a roll of canvas, ready to conquer the world. The world had other ideas, though; within a few short years I would graduate magna cum laude from the school of artificial enlightenment, speaking an entirely new language, consisting mainly of monosyllables, what was left of my artistic vision dissolved in mere hallucination. But I was cool. For one brief moment, I was cool.

Many of us bought into the dream that we were on the threshold of a new age, an age that could only be entered through the Doors of Perception; we arrogantly claimed the dubious title of aquarian pioneers, explorers of inner space; we believed we were going to arrive in a New World of Consciousness, and transform the old one from the inside out. Little did we know at the time, though, that reality didn't really give a shit. Pride goeth before a fall, they say. We were so blinded by the sunshine we didn't notice that the times were once again a'changin', the days were rapidly agin', and The Seventies were just around the bend. The dream that acid built was about to end, and for many of us it would not be a happy ending.

For some it was going to be a long, long way down.

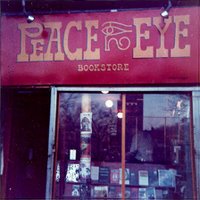

For some it was going to be a long, long way down.In the beginning it was all day-glo and roses. That first summer the Village was alive with artists, musicians, poets, activists, hippies and street wizards, right alongside the original inhabitants: ethnic Ukrainians, primarily - the only ones who weren't perpetually stoned. Peter Markett, a master furniture maker of the early American school of joinery who had come from northern Maine to seek his fortune, lived and worked in the storefront next to mine; we became good friends, often sharing coffee together in the morning. We were right around the corner from Ed Sanders' Peace Eye bookstore on Avenue A, where I used to drop in, shoot the breeze with Ed if he was around, even listen to him read aloud a song or a poem he was working on. He was still with The Fugs at that time; they called it quits the following year, I believe. Met Abbie Hoffman in there a few times, Wavy Gravy and others from the Rogues Gallery of the Sixties. Rick Sanders, a fellow drummer from Albany (no relation to Ed) had a head shop just off the park on A, but I can't remember the name. In fact, there's a great deal I don't remember about those days, so I'd better get back to what I do recall, before even that fades away.

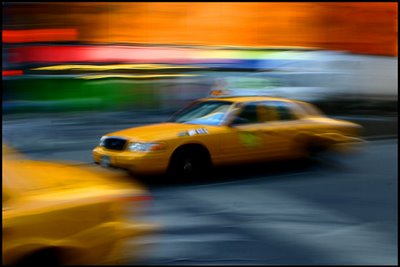

Back to that grimy yellow cab, in fact, and my increasingly dark and muddled thoughts. In the past month or so I had been robbed three times. I first lost my innocence walking through Tompkins Square Park at about 5 in the morning;

this guy jumped me from behind, grabbed me around the neck, held a broken bottle to my face, and whispered hoarsely in my ear, 'give me every penny you got, motherfucker, or I'll cut your fucking head clean off.' Never will forget those words. I politely allowed him to reach for my wallet, which contained a mere ten bucks. He was so pissed I thought he was going to cut something off anyway, but he took the money and ran. It took a little while to pick up my wallet with a shaky hand, then continued on my way to 10th and A, realizing I was not quite the same person coming out of the park as I was when I entered it. Near-death experiences are funny that way.

this guy jumped me from behind, grabbed me around the neck, held a broken bottle to my face, and whispered hoarsely in my ear, 'give me every penny you got, motherfucker, or I'll cut your fucking head clean off.' Never will forget those words. I politely allowed him to reach for my wallet, which contained a mere ten bucks. He was so pissed I thought he was going to cut something off anyway, but he took the money and ran. It took a little while to pick up my wallet with a shaky hand, then continued on my way to 10th and A, realizing I was not quite the same person coming out of the park as I was when I entered it. Near-death experiences are funny that way.The second encounter took place in broad daylight as I returned home from hanging out in Washington Square, headed east on 8th Street.

As I passed Tony Rosenthal's giant steel cube, "Alamo," which had recently been installed across from Cooper Union, I was suddenly surrounded by a gang of eight or ten guys you don't want to meet anywhere, anytime, even at high noon on a crowded sidewalk. Two of them grabbed me from behind, the others closed in on me, and one of them - I can still see those cold, vacant eyes - put his face up against mine and said 'gimme the jacket, asshole.' I said, 'What??' I said gimme the goddam jacket or you'll never need another one, mothafucka.' For some reason (male ego, I suppose), I said, hell, no. this is my jacket, why the hell should I give it to you?' Bad move. Bad, colossally stupid, move.

As I passed Tony Rosenthal's giant steel cube, "Alamo," which had recently been installed across from Cooper Union, I was suddenly surrounded by a gang of eight or ten guys you don't want to meet anywhere, anytime, even at high noon on a crowded sidewalk. Two of them grabbed me from behind, the others closed in on me, and one of them - I can still see those cold, vacant eyes - put his face up against mine and said 'gimme the jacket, asshole.' I said, 'What??' I said gimme the goddam jacket or you'll never need another one, mothafucka.' For some reason (male ego, I suppose), I said, hell, no. this is my jacket, why the hell should I give it to you?' Bad move. Bad, colossally stupid, move.Suddenly this otherwise unremarkable fellow, a suit and tie kind of guy, someone I would ordinarily go out of my way to ignore, steps forward, taps my assailant, who's now leaning even further into my face and turning purple, on the shoulder and says, 'excuse me. hey, can I talk to him for a second?' Amazingly, perhaps caught off guard, he backs off. The suit & tie guy pulls me aside and says, Do you know who these guys are?

No, I've never seen them before. They're the Alien Nomads, a gang of subway bikers*. They have to steal a denim jacket to get their colors in order to get into the gang. They were in the Times last week; a few of them beat a guy up, doused him with gasoline and stood around and watched him roast, just for kicks, over on Third Street. Oh. I see. Oh. Thanks, man. Thanks for telling me that. I turned around, took off my well-worn, well-faded and well-loved jacket, said my goodbyes, and walked away. Never looked back. By the way, I don't know who my guardian angel was that day, but I have never stopped thanking you in my heart. Muchos gracias, mi amigo.

No, I've never seen them before. They're the Alien Nomads, a gang of subway bikers*. They have to steal a denim jacket to get their colors in order to get into the gang. They were in the Times last week; a few of them beat a guy up, doused him with gasoline and stood around and watched him roast, just for kicks, over on Third Street. Oh. I see. Oh. Thanks, man. Thanks for telling me that. I turned around, took off my well-worn, well-faded and well-loved jacket, said my goodbyes, and walked away. Never looked back. By the way, I don't know who my guardian angel was that day, but I have never stopped thanking you in my heart. Muchos gracias, mi amigo.*'Subway bikers' was the term de jour for gangs like the Alien Nomads, who lived the lifestyle of the Hell's Angels but couldn't afford motorcycles, and made their mark on the city by terrorizing subway passengers in the late '60's.

To be continued.....